Writing Tool Critique: Storyspace

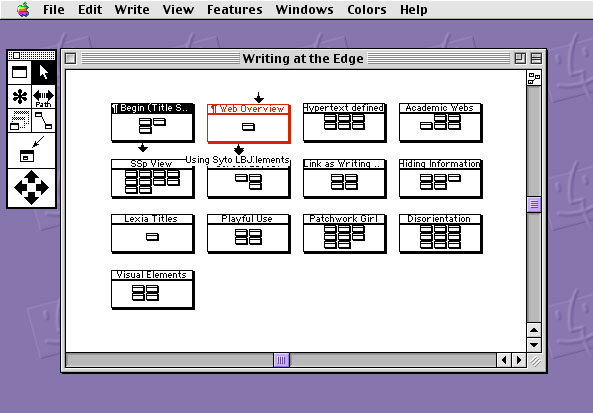

Figure 1: StorySpace running George Landow’s Writing at the Edge

|

Storyspace: Michael Joyce’s Afternoon, A Story In an effort to expand my LIT 2101 students’ conceptions of what narrative is, I introduced them to several "postmodern" texts that play with fragments and spatial and temporal orientation, e.g., Borges’ “The Garden of the Forking Paths,” Gibson’s "The Gernsback Continuum," and Ballard’s "The Enormous Space" and "The Index." After this introduction to the "readerly" text, I assigned Michael Joyce’s hypertext Afternoon, A Story. Joyce’s hypertext uses Storyspace, a hypertext generator program (see Figure 1). Storyspace may be used much like Macromedia’s Director in bot creating and using both multimedia presentations or texts. Since my class used Storyspace only to read Afternoon but not to write their own hypertext, I will concentrate on the hypertext itself, the software environment in which it’s used, and student reactions to the experience. Afternoon’s narrative centers around the events of a single afternoon in the lives of the four main characters: Peter (the narrator), Wert, Lisa (Nausicaa), and Lolly. A single incident changes the lives of the four, especially Peter, that the reader (user) eventually discovers: the car accident that kills Lisa, Peter’s ex-wife, and Andy, Peter’s son. The rest of the hypertext concerns itself with the characters’ interaction, based most on their sexual promiscuity and intraoffice politics. All four work for Datacom, an information provider for big businesses; Wert supervises the others; Peter and Nausicaa work in "Validation;" and Lolly is a secretary by day and a prostitute by night. Much of the text presents discussions of sex and the characters’ shallow and abortive relations. Storyspace presents Afternoon on a series of narrative cards that are connected by various links (see Figure 2). The bar at the lower portion of the screen contains navigation tools. Clicking the left arrow takes the user back to the last card, much like a Web browser; the icon of a book allows the user to select his/her next link by their titles (see Figure 3); another choice is represented by the "Yes/No" button: click the top to answer yes to a posed question in the text, the bottom to answer no. The largest box is a text entry box, letting the user enter any word or words that occur to him/her while interacting with the text. Sometimes these words produce positive results, sometimes they propel the user into an entirely new situation. Finally, one may follow a link by double-clicking on an interesting word within the text, but, like using the text box, sometimes clicking on random words produces confusing results. Storyspace is much like Apple’s HyperCard, one of the first hypertext applications written for the personal computer. By using the card metaphor, Afternoon is a closed hypertext, or one that does not link to material outside itself. Referring to Figure 1, Storyspace sets up hypertexts like rhizomes–one has the use of the entire surface areas (or “plateaus”) and different levels in which to work; links can be set up to take the user to the same level, or any of the various levels of the hypertext. Thus the story exists, much like a traditional narrative, yet it is fragmented into episodes that are scattered throughout the rhizome and requires the user to make connections and order the story so that it makes sense. Interestingly, depending on how one interacts with the text, the story, based upon its construction, actually becomes an entirely different work, highlighting different scenes and characters, circulating and alluding (eluding) the central event, so that not only the themes, but the content of the story is different for each user and subsequent reading of the text by the same user. Indeed, readings of "traditional" stories change from reading to reading (and reader to reader) based on affective response, but Afternoon highlights this process by its very form(-lessness). Here are some student comments:

Even though Afternoon’s interface takes a bit of getting used to (read it on an LCD, not a CRT), it does pull one in just like a well-written piece of prose. As several of my students suggested, Afternoon demands a greater commitment and concentration than do traditional narratives. Many students commented that this fact was a negative aspect in their experience, but several imply, what one student articulates well: "Through frustration, with persistence, we will learn, and maybe, because of this fact, the negatives are also positives." Indeed, Afternoon, if taken seriously and persistently, may help students develop the necessary skills for critical and thoughtful reading. I taught Afternoon at the end of the semester this year, but I think I’ll begin next semester with it as an exercise in the active engagement of the text. Some Key Lexias from AfternoonStoryspace, Afternoon, A Story, and many other hypertexts are available from Eastgate Systems. |